The One After Moby-Dick: Melville's Pierre; or, The Ambiguities

David and I read an 1852 novel about one of the most annoying 19-year-olds ever.

Every so often, the urge to dive into a 19th century novel reasserts itself with a vengeance. I love a project of a book, though often am oftentimes overambitious in scope (I write, two years and 600 pages later, having avowed to read War and Peace in 2022 – I’ll finish it eventually). As a person, I am prone to sweating the small stuff, and find solace in the 19th century writers who do the same in their work. Your fate might hinge on deciphering your late father’s inscrutable expression rendered in his portrait! Making eye contact with a certain girl at the sewing party might ruin your life!

One of my favorite parts about reading books is talking about them with people I like, and so I floated the idea of reading a lesser Melville to my friend, film critic and former English major David Sims. Together, we waded into the angsty, overwrought waters of Herman Melville’s Pierre; or, The Ambiguities.

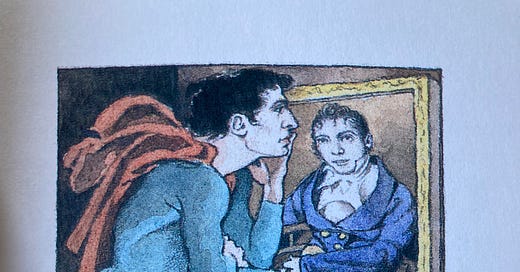

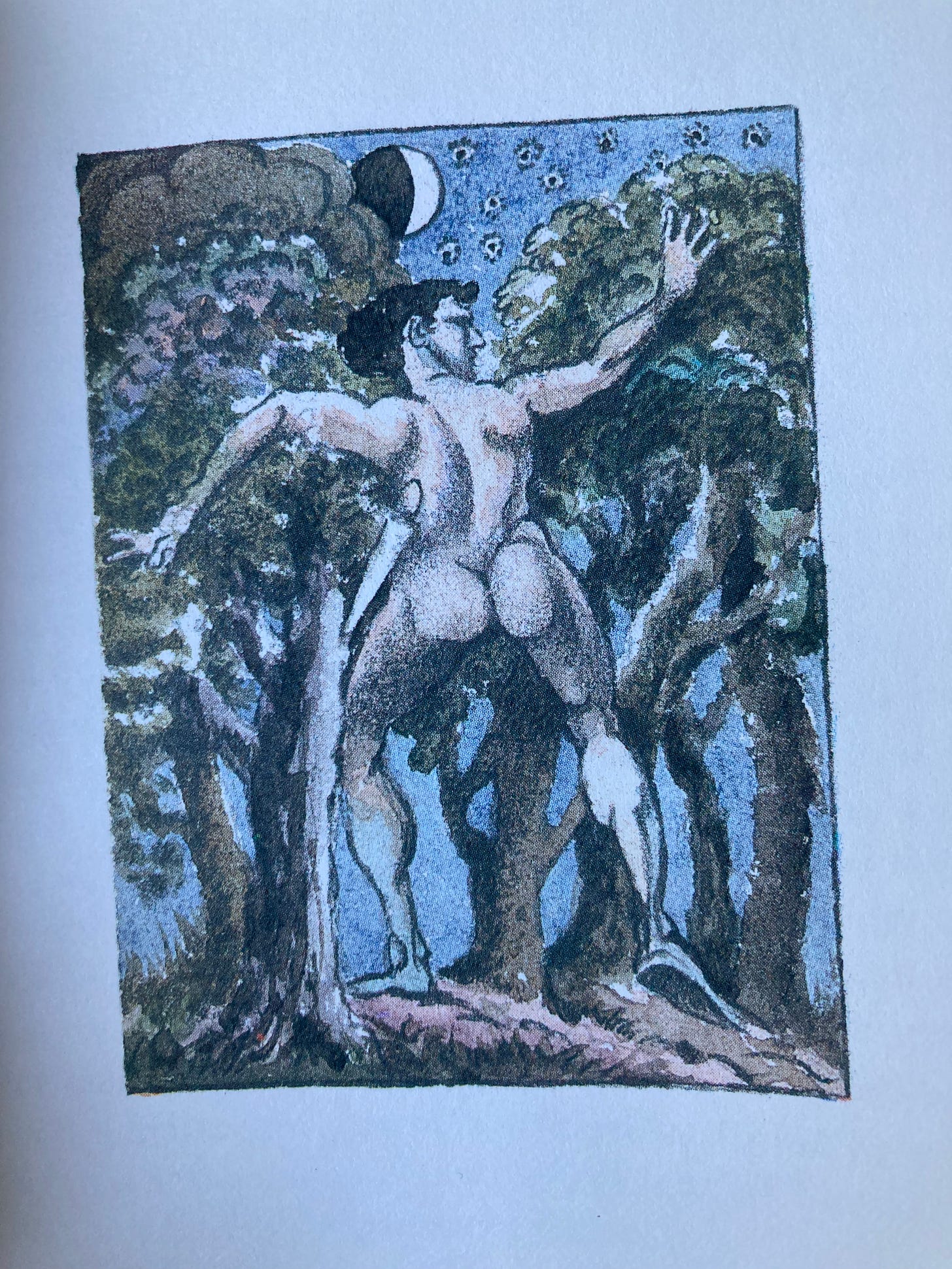

^ Maurice Sendak illustrated a version in the 90s — more on that later.

This 1852 follow-up to Moby-Dick depicts our hero, 19-year-old Pierre Glendinning Jr., as he learns of the existence of an illegitimate half-sister Isabel. Naturally Pierre pretends to marry her.1 Together they, alongside disgraced maid Delly, decamp to New York City, where Pierre pursues writing and whining. Here, we talk plotting (or lack thereof), emo freaks and rural bowls of milk. Enjoy!

Carolyn Ten Eyck: We decided to read this book because we both like Moby-Dick? I think? And I wanted to read another Melville besides Moby-Dick. You’ve read Billy Budd as well, which I know about to the extent of the Sopranos bit about it. How does Pierre compare?

David Sims: I read a bunch of Melville in college – shout out to my 19th century American lit class at Newcastle University, where reading American novels was seen as a fun and quaint distraction from the grand old canon. We read Moby-Dick (love forever, especially all the “fact” parts that are like “whales have seventy stomachs, enjoy tea only in the afternoon, and tend to follow the Greek Orthodox faith”). We read Billy Budd, an iconic entry in the genre of “what if there was someone so hot you actually went insane.” And we read his stories “Benito Cereno” (harrowing, v good, no jokes needed) and “Bartleby the Scrivener” (maybe his greatest masterpiece, an exegesis on quiet quitting, I named my first car “Bart” in its honor).

I think I was possibly supposed to read Pierre too, and didn’t. It was either that or The Confidence-Man. But I own a UK Penguin Classics edition of Pierre which suggests it was a neglected part of my syllabus. Sorry to the professor who I remember doing a very fun re-enactment of a chapter of The Last of the Mohicans once. It’s why I leapt at the suggestion when you floated having an impromptu book club and reading a Melville. I wonder how Pierre would have felt alongside all of those texts; a little baffling, but fascinating. It’s definitely best consumed last, as Melville seems intent on bleeding almost all of the plotting out of his work by then.

CT: I was predisposed to love this book because it begins with Melville dedicating the text to Mount Greylock, the highest point in Massachusetts — a twist on the fashion of dedicating a book to British royalty, he devotes Pierre to “Greylock’s Most Excellent Majesty” — such a snotty and fun move.

He wrote this novel while living in his farmhouse in Pittsfield, MA after pulling the classic ‘leaving New York City’ literary maneuver. Initially, Melville thought to market this book to female readers, describing it as a “rural bowl of milk” and floating the use of the nom de plume “a Vermonter,” presumably to add some folksy flair. This framing feels disingenuous to me, given what happens in the back end of the book, but how does it strike you?

DS: Perhaps he intended it as a manual for female readers at the time to better understand why men are so irrational and exhausting. Or maybe this is just his take on a serialized, soapy drama of manners and high society. I know he was inspired by Benjamin Disraeli, who wrote a wonderful book a few years prior called Sybil that is a very blunt bit of in-yer-face storytelling about how rough it was being poor in 1840s Britain (spoiler: it sucked). But I struggled to really map the inspiration on here, even though Pierre does depict scenes of squalor and the like, because the writing style is just so chaotic. If it’s a rural bowl of milk, it’s being hurled at you from horseback.

CT: He’s a wonderful writer (hot take), which was enough to distract me for the first hundred pages or so that nothing was happening. I spent the first half of the book dying for the plot to kick into gear; for Pierre to stop his adolescent agonizing and make a decision, and the second half missing the mooring of the first half’s setting.

DS: If Pierre lived in 2024 he would have a podcast, or at the very least a Substack, and all his blathering about not feeling horny enough for his boring fiancee could maybe go there. Anyway, yes, I do think I was thrown by how the opening chunk of the book imitates the setup of so many a Victorian novel of life in a big house that I’ve read and loved; I kept waiting for intrigue to kick off with the farmer next door or the mean lords over the hill, instead Pierre seemed to spend 50 pages deciding whether to even go outside. He’s such a lame freak.

CT: I know there’s a shroud of sexism about it all, but I love the buckwild descriptions Melville gives to his female characters. Of Pierre’s mother, he writes “litheness had not yet completely uncoiled itself from her waist, nor smoothness unscrolled itself from her brow, nor diamondness departed from her eyes.” Of Lucy Tartan, Pierre’s fiancee? “Her teeth were dived for in the Persian sea” and eyes gazing “as two stars gaze down into a tarn.” She has a “violet young being” - a violet young being!! I’m so charmed by it all.

DS: Yeah, Melville can write, even when he’s decided to forget how to plot. And it does lend the right sense of mania to Pierre’s headspace; feels like he’s over-analyzing everything he sees.

CT: This book was met with an overwhelmingly negative response (though let us remember Moby-Dick was also not received to universal acclaim). A reviewer in the New York Day Book wrote a pan entitled “Herman Melville Crazy.” I know you don’t write your own headlines, but as a critic, what are your thoughts on this framing? Herman Melville crazy?

DS: I wish I could do this more often. Madame Web Crazy. Paul Schrader Crazy (in a good way). Etc. etc. Yes, I think Melville was a little crazy. It’s funny how Ben Whishaw plays him in In the Heart of the Sea (a film only I saw), basically as an emo sweetie pie with a few simple questions about a whale this one sailor saw. No way Ben – he was crazy.

CT: Digging into adaptations of Pierre, Maurice Sendak illustrated the semi-controversial 1995 ‘Kraken edition,’ which edits out much of the third act’s focus on Pierre as a writer. Leos Carax made Pola X (1999), which we watched and was pretty unstimulating. Why was Pierre fever burning so hot in the 90s? Are adaptations of this work doomed to fail?

DS: I can see why Carax was drawn to it for sure – the subject matter is so transgressive on the page, even as Melville dances around the lurid details. But then I was baffled by how low energy and miserable so much of Pola X actually was, especially given that Carax is one of the most electrifying filmmakers alive. Perhaps he was challenging himself in some late 90s way to be boring and not have lights on set and stuff, that was very hot back then (as was unsimulated sex). You have been sending me pictures of Sendak’s edition, which seems like maybe the best adaptation of them all, i.e. largely focused on how this guy has a weird floppy penis and struggles to ever stand on his own two feet. Pierre. Such a freak.

Herman Melville also had a woman claim to be his illegitimate half-sister after his father’s death. Autofiction alert